King Tut is in the news again–not regarding his supposed “curse,” but as the subject of high-tech analyses that debunked his supposed “murder” and provided a more realistic representation of the youthful king’s features.

In his book, The Murder of Tutankhamen, Egyptologist Bob Brier had claimed to solve the 3,000-year-old mystery of the teenage pharaoh’s death. Citing forensic evidence he concluded that Tut was the victim of murder, probably by his chief advisor Aye, a commoner, who then married Tut’s widow, Queen Ankhesenamen. According to Brier, “The X-ray of Tutankhamen’s skull suggests a blow to the back of the head.”

Given my background as a former private investigator and investigative writer who has been involved in several death investigations, as well as co-author of the forensic textbook Crime Science, I have followed the “murder” case with interest. I was skeptical of Brier’s conclusions, although very sympathetic to his attempt to apply forensic and historical evidence to an ancient mystery.

Brier’s conspiracy theory had many arguments against it, beginning with the uncertainty that there was a blow to the back of Tutankhamen’s skull. At most, it was a single blow and was probably not immediately fatal, meaning he had lingered for a time, Brier conceded. Moreover, a bone fragment inside the skull was believed to have been dislodged post-mortem, during mummification. Skeptics observed that even if there had been such a blow, and that it had eventually led to the pharaoh’s death, it could have been the result of an accident rather than murder.

Now, sophisticated computer tomography (CT) scans by Liverpool University anatomists have disproved the blow-to-the-head murder scenario. More revealing than conventional X-rays taken in 1968, the CT scanning involved 1,700 digital images taken in .62-millimeter “slices” to produce a three-dimensional anatomical record of Tutankhamen’s remains.

Summarizing the results, Zahi Hawass, head of Egypt’s Supreme Council of Antiquities, stated, “The team found no evidence for a blow to the back of the head, and no other indication of foul play.” The bone fragment–actually fragments, as revealed by the CT images–apparently came from the royal funerary workers having drilled a hole in the skull so that the brain could be pulped with an instrument and removed, and embalming resins could then be poured in.

However, the new investigation did not solve the mystery of Tutankhamen’s death. The remains of the slightly-built, five-and-a-half-foot-tall, approximately nineteen-year-old pharaoh revealed no specific cause of death. Poison was not ruled out but would require other analyses to be detected.

Nevertheless several possible causes of death remain:

The effects of an apparently ante-mortem broken right leg. This might have become infected and thus have contributed to Tutankhamen’s death. Some experts, however, believe the fracture was caused after the 1922 discovery of Tut’s tomb by British archaeologist Howard Carter. (Carter’s anatomist, Dr. Douglas Derry, found that congealed oils had glued the mummy into its coffin and he had to cut it in half and chisel it out in sections.)

The result of plague. After Tut’s death, his young wife Ankhesenamen soon also went missing from the historical record and may have died. Significantly, after a Hittite prince who had come to marry the widowed queen was murdered, the Hittites attacked Egypt and brought back prisoners who soon died of plague. The disease then spread and persisted among the Hittites, according to an ancient text. Possibly, some speculate, Tut and his wife had succumbed to the same plague.

Chest trauma. The mummy’s chest is mangled, the breastbone being missing along with part of the front rib cage. Dr. Derry had not observed this because of the black-resin-coated linen covering the mummy’s chest, so it seems unlikely the bones were removed then. Some have suggested that the missing bones resulted from an accident or intentional violence that killed the young pharaoh. Writing in National Geographic (June 2005), A. R. Williams has asked, regarding the bones, “Did the embalmers take them out while preparing a gravely injured Tut for eternity?”

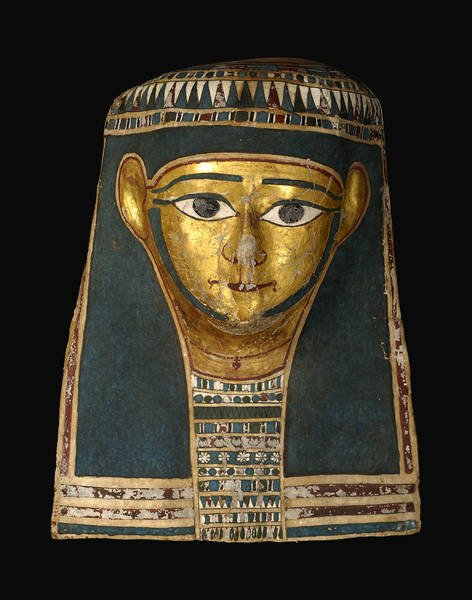

While many such important questions remain, science continues to provide other valuable information. For example, the CT scans also enabled forensic artists to reconstruct Tut’s head and facial features, showing an elongated skull, pronounced overbite, and weak chin–a more realistic depiction than the stylized one on his golden funerary mask.

As to the so-called “mummy’s curse,” it seems no longer operative. In fact the inscription, “Death shall come to he who touches the tomb,” was non-existent. In 1980, the site’s former security officer admitted the story of the curse had been circulated to frighten away would-be grave robbers. Balancing the list of misfortunes touted by curse proponents is the fact that ten years after the tomb was opened, all but one of the five who first entered it were still living. Carter lived until 1939, when he was sixty-six, and Derry lived to be over eighty years old.